Though I love their music, I was too young to experience The Beatles firsthand. For that, I depended on older relatives to school me. I was five when Let it Be came out, so although I remember singing along to the title track and “The Long and Winding Road” with my Aunt Lois and her friends, I wasn’t old enough to appreciate either of those songs or The Fab Four’s musical genius until a few years later.

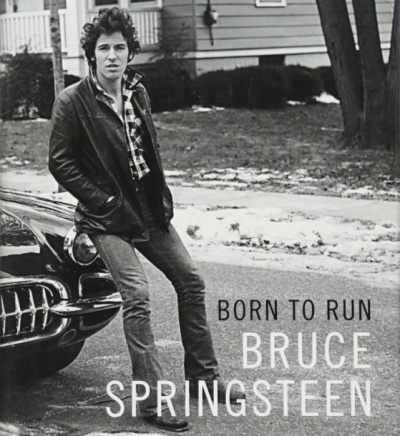

Fortunately, I was a bit more lined up time-wise with Bruce Springsteen. I was ten when Born to Run released, though I remember loving the title track but not noticing much else about the album. A few years later, when the double album The River appeared—somehow I’d missed Darkness on the Edge of Town—fifteen year old me ate it up from start to finish and scampered back to Born to Run to do my homework.

By the way, there’s a lot to love in the Bruce Springsteen catalog, but for pure quality, it’s tough to do better than Born to Run. It’s the one I always return to when I need a healthy dose of rock and roll grandeur. Sure, it’s the one of the two of his albums everyone can name, but there’s a reason for that.

Of all the musicians and songwriters I admire, Springsteen has probably had the most significant influence on me as a writer, musician, and person. That’s high praise, because, as you may know, I’m kind of a music guy. No one does futility, hope, audacity, and heartbreaking optimism like The Boss. He took the staples of fifties and sixties rock music—cars, girls, beaches, outsiders, desperation, the power of a well-aimed guitar—roughed them up for a new generation, claimed his spot as The Next Big Thing, and made it look easy.

When I think of Bruce Springsteen’s body of work, I inevitably remember these lines from one of my favorites, his song “Jungleland.”

Outside the street’s on fire in a real death waltz

Between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy

And the poets down here don’t write nothing at all

They just stand back and let it all be

When I recall that line—which happens more often than you might think—I’m glad Springsteen decided to write it all. Or most of it, anyway. He’s still got time to write more.

Now, I can’t imagine what my life would be without the songs: the rollicking and exhilarating “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)”; the playful rhyming patter of “Blinded by the Light”; the novel-disguised-as-a-song “Thunder Road”; the soul-infused “Tenth Avenue Freezeout”; the utter desperation of “Backstreets”; the rock and roll battle cry of “No Surrender”; the sweeping, majestic noir of “Jungleland.” And those are just the songs I could come up with on a deadline with a word count.

For years, music critics, publicists, and diehard fans like me have preached the gospel of Springsteen. His songs are stories of working-class souls, loners, and misfits, the there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I protagonists who have no choice but to take one last chance that probably won’t work, but it doesn’t matter anyway. His lyrics are the poetry of the mundane and the everyday people, places, and dusty and sweaty elements of American life. His shows are legendary four-hour events more like old time tent revivals than rock concerts. His crew, The E Street Band, is one of the finest rock and soul outfits ever assembled.

Those are all Springsteen cliches, every last one of them, enough so that they’ve come to seem almost meaningless. They’re also all true.

A few years after The River and its follow-up Nebraska, in 1984, I joined the U.S. Navy and spent most of May, June, and July in boot camp. When I emerged as a newly minted machinist’s mate, imagine my surprise when I laid ears on Springsteen’s radio hit-laden juggernaut Born in the USA. Don’t judge me too harshly for my ignorance about the new album, either. Those were the days before fans could keep track of their musical heroes’ daily lives, recording schedules, and favorite health remedies on social media.

Just in case you weren’t around when Born in the U.S.A. released, it was everywhere. There were at least four MTV videos—one of which featured a young, pre-Friends Courteney Cox—radio singles as far as the ear could hear, and dance club remixes. It even carried the distinction of having then-President Ronald Reagan very publicly misunderstand the lyrics of the title track. When The Gipper flubs your song’s meaning to all of humanity, you know you’ve made it.

Born in the U.S.A. was so successful, in fact, that a few of my navy friends who were Springsteen fans dismissed it outright, the logic being if that many people like it, it can’t be good. Hey, they said—sounding so hip it must’ve been painful—I liked Springsteen before it was cool to like Springsteen.

If I’d been a Bruce fan before, after Born in the U.S.A. I became a downright evangelist. Every band I played in had to feature some Springsteen tunes, preferably ones in my vocal range, like “Glory Days,” “Cover Me,” “Atlantic City,” or “The River.”

Then, as so often happens, a lot of years passed. Springsteen albums and songs came and went, both without the E Street Band (okay) and with them (best). He won an academy award, continued to inspire the hell out of a couple of new generations of musicians, and got older. But then didn’t we all?

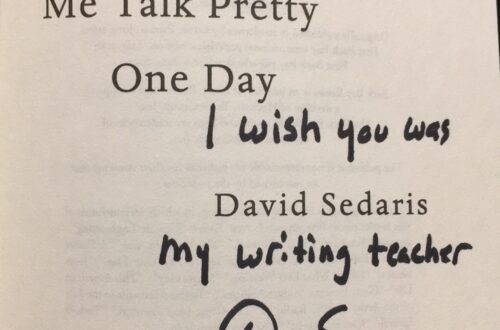

Two years ago, Springsteen wrote a memoir with the catchy title Born to Run, and I put it on my reading list. Life continued to happen, though, so the book never seemed to make it onto my bedside table. It took a while for me to get to it, but when I did, man, I devoured it.

There’s something immensely satisfying about knowing what inspires your creative heroes. What was Bruce thinking about when he wrote “Thunder Road”? (Turns out he was disappointed because he couldn’t sing like one of his heroes, Roy Orbison.) How exactly did the classic E Street Band lineup come together? (Spoiler Free Answer: It was a long and surprisingly complicated process.) Why did I miss the release of Darkness on the Edge of Town? (As it happens, there’s a good reason for that, but it was my own fault.)

There were also a few surprises in the book, one of them how Springsteen has never considered himself a singer. Sure, I know a lot of others don’t consider him a singer—both fans and non-fans alike—but he’s always owned that rough-ass voice so hard that I just knew he knew he was a singer.

Another surprise is learning about his shock at the success of Born in the U.S.A. To me, that album just sounded like he wrote it to be a smash, like he’d reached that point in his career where it was, you know, his turn, and the rock and roll gods bestowed upon him a songlist to take the world by storm.

If I have one complaint about the book, it’s that I’d have liked more incidental stories. I mean, he didn’t even talk about the story behind “Fade Away”—one of my favorites from The River—or how he originally wrote “Hungry Heart” for The Ramones. What’s up with that, Bruce? Fans want the details.

Be warned: This memoir is for the true fan only. If you want to know the minutiae of Springsteen’s life, it’s the book for you. If not, you probably already know everything you need to about him from the albums, or at least you think you do, and that’s probably okay.